When I was in college, I had an unusual hobby. I, a cradle Episcopalian, scoured the Internet for examples of Episcopalians and other mainline Christians acting foolishly: liturgical shenanigans, theological absurdities, and ham-fisted political statements. These were not hard to find. Whole blogs seemed devoted to assembling and uplifting some piece of nonsense a clergyperson had said, or publicizing the goofy alterations a parish in the Diocese of Who-knows-where had made to the Book of Common Prayer. I savored each one with a mixture of humor and adolescent defiance. What a joke, I though, over and over. This is the Episcopal Church?

Now, I had never experienced anything similar. My home parish, in the Diocese of Pittsburgh, had several Sunday services, all of which followed the prayer book. We sang traditional hymns, with the organ and choir, or sometimes more modern music with a small praise band. We said the Nicene Creed, and in Sunday school I learned what it meant. I was baptized by a faithful priest, catechized by dozens of faithful teachers, and confirmed by a faithful bishop. I was a VBS participant and volunteer, an acolyte, a mission tripper, and fish fry waiter. I played Joseph in the Christmas pageant and William Tyndale in an All Saints play. My Eagle Scout project was creating a community garden at a neighboring parish, a garden which still produces fresh vegetables for the food bank today.

The church’s preaching, as far as I can remember, was wholly unremarkable, sometimes inspiring and sometimes a little dull (at least to my teenage ears). If we didn’t have Spurgeon, we certainly didn’t have Spong. Just faithful clergy trying to proclaim God’s Word and explain why it mattered. The Episcopal Church, in the form of this congregation, had been good to me, in every way the mother of my faith.

But I was restless. I was 19 or 20, and none of the things I listed above seemed to matter. This was, I think, for two reasons. First, I was studying theology at a Roman Catholic university. The great edifice of Catholic scholarship, taught with joy and rigor by Jesuit professors, made my teenage catechesis seem insignificant. Here was the real stuff. I never quite acknowledged that a systematic theology class of any kind, taught by an internationally-renowned theologian, would be more intense than confirmation at 14!

But beyond the intellectual heights, the Catholics I met seemed so serious. They went to Mass, every week. They served the needy. They knew their own tradition, and they loved it as a living stream from which they drank. I compared them to my own faith, which felt so lackluster and anemic, and concluded that the problem had to lie with my childhood church. If I rarely attended services, well, that was because the Episcopalians hadn’t trained me up well enough. So the first reason for my dissatisfaction was church envy.

The second reason was the above-mentioned diet of horror stories about the Episcopal Church. Collecting and sharing these stories was and is a cottage industry among a certain set of conservative Protestants and Roman Catholics. I am sure you know the type. “Episcopal priest communes dog,” that sort of thing. The latest inexplicable adoption of pop music as a Mass setting. All manner of creative rewrites of the Lord’s Prayer. And, of course, continual reports that the Episcopal Church was shrinking- fewer baptisms, fewer attendees, fewer seminarians- tied, no doubt, to all this laughable liberalism.

These abuses loomed much larger in my mental picture of the church than my actual, flesh and blood experiences, which I had taken so much for granted as to make them almost invisible. It took regular attendance and participation at other Episcopal parishes, and experiences of divine love and power there, to cure me. As an adult, I have witnessed God’s forgiveness of sins, his grace mediated through the sacraments and the preaching of the Gospel, and the corresponding faith of his people, my fellow Episcopalians. I witnessed the tremendous energy, the Spirit-filled missionary work of other seminarians and clergy. And all this is so immensely, immediately real that the nonsense I see online- and there is a great deal of it- no longer moves me. The careless or mistaken words of clergy across the country no longer rattle my faith, either in Jesus Christ or in the little institution called the Episcopal Church.

What I came to realize is that every church larger than one congregation has problems. No matter how orthodox and loving your parish is, and no matter what denomination you are, other members of that denomination are up to some nonsense somewhere. The Internet allows us to find and focus on the nonsense instead of resting content with our real-life experiences of an imperfect, faithful church.

For example, one of the largest parishes in the Anglican Church in North America, LA’s Vintage Church, has no commitment to infant baptism and describes being born again as something that “can only be [a person’s] decision when the time is right.”1 This is, to put it mildly, extremely divergent from the last 500 years of Anglican tradition, as well as the lion’s share of Christian practice before the Reformation. None of the magisterial reformers would have regarded it as adiaphoral.

And yet there is, to my knowledge, no blogosphere devoted to exposing, naming, and shaming such deviations from Anglican orthodoxy, nor suggesting that Vintage represents ACNA as a whole. It surely does not. If someone is satisfied with their ACNA parish, it would be absurd for them to leave just because some people in LA have baptism all wrong. The same is true for the click-baity Episcopal horror stories that used to distress me so much. In any denomination with thousands of parishes, you’ll be able to find silliness and error of one sort or another.

Martin Luther realized this, long before the Internet gave us the power to outrage ourselves whenever we wished. As a theologian, his influence extended across Europe. But his focus remained the church in Wittenberg, the community of Christians to which he preached the Word and in which he experienced Christian fellowship. He was not responsible for what happened elsewhere; God would take care of that.

I dare not preach without a call. I must not go to Leipzig or to Magdeburg for the purpose of preaching there, for I have neither call nor office to take me to those places. Yes, even if I heard that nothing but heresy was rampant in the pulpit at Leipzig, I would have to let it go on. It is none of my business, and I must let them preach. I have not sowed there. Consequently, I am not entitled to harvest there.2

Now, Luther puts it a bit strongly. I think it is all of our business what is preached in other Episcopal pulpits, in the sense that we should care and should use what influence we have to encourage sound doctrine and practice. But he is quite right that we are each called to be Christians in a particular local church, either as clergy or laypeople. We aren’t called to be ‘Christians at large,’ constantly worrying about what is going on in the next diocese over. And most us aren’t called to be inquisitors, zealously checking whether anyone has deviated from our own beliefs or worse, preferences.

So my advice to Episcopalians and others who may be distressed by what they see online is don’t give up the ship. Don’t allow your impressions of the larger Episcopal Church- the latest shenanigans- to outweigh what you experience in your own parish: the Word, sacraments, and fellowship of Christ’s people. Don’t allow something silly miles away, or even worse, a dumb tweet or Facebook post, to choke your living faith. Be all means, strive for the truth in theology, liturgy, and social witness. Mourn and protest when the church fails messes up (as it often does). Reprove when you can. But don’t let the online outrage machine set your agenda, and don’t let someone else’s errors rob you of your joy in the Gospel.

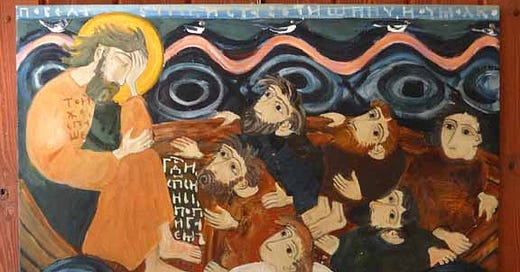

![Title: Christ Sleeping in the Storm

[Click for larger image view] Title: Christ Sleeping in the Storm

[Click for larger image view]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!_nEy!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F8229b66d-20ac-447e-b1d9-eaaeb202fbf7_576x413.jpeg)

I’ve found the following rule helpful: when something online makes you despair of TEC, ask yourself “Would I have even been aware of this if I lived 50 years ago?” If not, then work to change it, but don’t let it alienate you from “the doctrine, discipline, and worship of Christ as this Church has received them” (BCP 526). The Internet tempts us to think it is more real than real life. But the church is a flesh-and-blood, human thing that lives in your local congregation, not in little clips from a faraway sermon or in outraged articles online.

John Keble said that “If the Church of England were to fail, it would be found in my parish.” Perhaps we can say that if the Episcopal Church were to succumb to silliness, it would be found in each of our parishes, quietly baptizing and preaching the Word. Or at least, we can pray that it will be found so doing. Amen.

https://www.vintagechurchla.com/baptism

Martin Luther, “Sermons on the Gospel of St. John,” LW 23, 227.

Good post. I think people are all-too-willing to leave their churches over what some people *over there* are doing, but that's a habit you can cultivate anywhere, and probably will once you jump ship. I find the norms of internet Orthodoxy to be embarrassing now, and it would be easy for me to just cultivate an internet presence of condemning various errors, but what good would it do me? I never see that stuff in my parish, or from my bishops, anyhow.

Conversion should come from some place of deep, inner conviction, not fleeing an image of dysfunction that is out-of-joint with your everyday experience.