From time to time, I have to go to the attic storage room above our parish hall. Inside are objects from the last 75 years of the congregation’s history: photo albums with much younger faces of parishioners I know, brochures about Cursillo and Alpha, dusty chasubles kept far away from our low-church sanctuary, a box with a tambourine and another with handbells, and even a broken hotdog machine from some long-forgotten fellowship event. Someone put each thing there, because they thought it might be useful someday, and each thing has some small story to tell. If you put them all together, you might learn the whole story of the parish. But with so many objects, it’s hard to know where to start listening.

I am reading Jürgen Moltmann’s autobiography, A Broad Place, as part of a deeper dive into Moltmann this Lent. Moltmann died last June at the age of 98. The book reminds me of the church attic, because it is full of snapshots and anecdotes, each of which hints at a larger story. Like the attic, it is overstuffed.

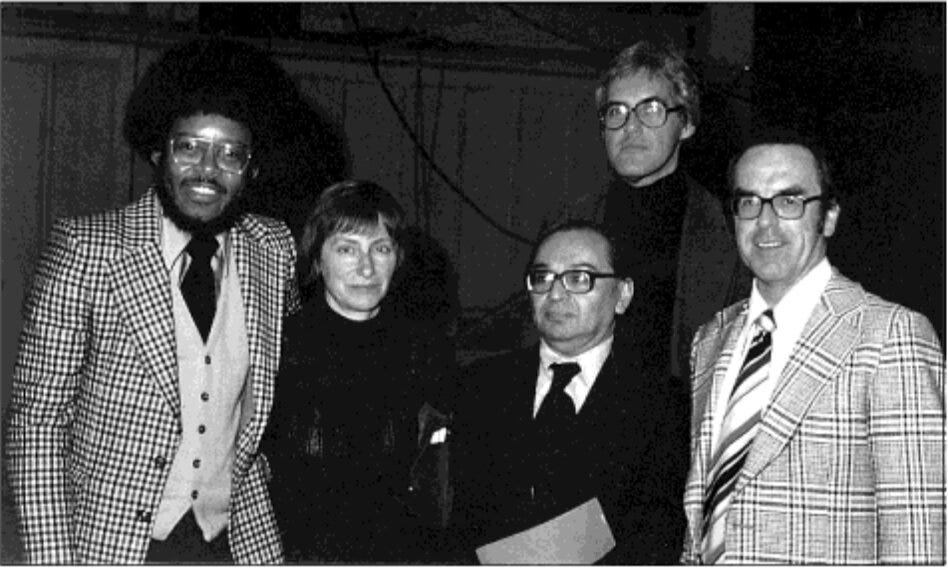

It contains encounters with other theologians. These include teachers, like Otto Weber and Hans Joachim Iwand, and contemporaries, like James Cone and Ernst Käsemann. It contains personal memories of a childhood spent in a kind of utopian, agrarian project, service in the Second World War, captivity in Britain, being found by Jesus Christ in a POW camp, romance and marriage with Elizabeth Wendel, and fatherhood to five children. It contains retrospective explanations of Moltmann’s major works and theological evolution, as well as excerpts from newspaper articles and ecumenical dialogues. It contains an impressionistic travelogue: shame in having to part ways with Bishop Tutu to enter the whites-only airport in South Africa; confusion at American college football during his year at Duke University; and unsuccessful meditation at a Zen Buddhist monastery in Japan. “It was cold,” Moltmann writes, “and I was frozen through…What I experienced was not enlightenment but only the chattering of my teeth.”1 And it contains passing comments, observations, and reflections, some humorous and some serious, as the older Moltmann looked back on all he had seen and experienced.

There is simply too much in the book for the reader to draw one conclusion, one ‘point.’ And there are far too many interesting tidbits and digressions for me to think through all of them to my satisfaction. I think this must be the case for any memoir worth reading, from Augustine’s Confessions down to one of my favorite books, James Boswell’s Life of Samuel Johnson. Biographies describe human lives. They are not novels. There is no ‘point,’ no single moral to a life. A life does not exist so that it can conclude in a satisfactory way; things do not occur in one’s childhood so that they can foreshadow future developments. They just happen. Of course, we can find meaning, draw out lessons, and connect the dots, but that always means trimming out extraneous details and massaging things into a coherent ‘plot.’ And there is nothing truly extraneous, nothing irrelevant to the ‘plot’ of a person’s life, because a life just is everything that happens in it.

The temptation to self-novelize is strong. We want our lives to make sense, for things to follow one after another so that we can look back and say “Ah, this was how it had to turn out.” Sometimes people ask me when I first felt called to be a priest, and I feel the temptation to answer “Oh, ever since I was a kid. I used to repeat the Eucharistic prayer after we left church on Sunday morning.” And this is true: I remember doing that, and happily babbling out “Take, eat…”. But it was probably only once or twice, and when I was eight or nine I suppose I did a lot of other things that might have pointed in a lot of other directions. But when I tell the story of my life, I leave out what seems extraneous, what doesn’t fit, and what is ordinary or boring. I concentrate on the big things, the turning points, and what fits the ‘plot.’ And this is necessary- no one wants to hear a chronicle of every day that I’ve spent on Earth, especially when a lot of them would just be “Well, I answered emails and took a walk.”

But this means that our life story, the story we tell to other people and even more that we internalize, cuts out most of our lives. Each life story is more like a collection of highlights or formative memories, the things that made up ‘who we are,’ set against the backdrop of all the normal days and sidetracks that don’t quite make sense. The random things, the chance and humdrum, have no place in a well-written novel or a well-ordered personal history. Like all those objects in the church attic, most of our memories get forgotten because we don’t have much use for them. They don’t seem to matter to the big-picture ‘plot.’ If they did, they wouldn’t have ended up in the attic, covered in dust.

All this reminds me of something Moltmann wrote about the resurrection in another book:

Hope for the resurrection of the body is not merely a hope for the hour of death; it is a hope for all the hours of life from the first to the last. It is directed, not towards a life 'after' death, but towards the raising of this life…What is spread out and split up into its component parts in a person's lifetime comes together and coincides in eternity, and becomes one. If what is mortal puts on immortality, its mortality is ended and everything past becomes present.2

Resurrection, in other words, is not just something that happens to the ‘finished product’ of the person each of us eventually becomes. It’s not that I develop, over my life, into the real Jack, who then gets raised up after I die and goes on to live forever and ever. That would mean that most of my life gets forgotten and left behind. No, the resurrection brings hope for “all the hours of life,” the momentous ones and the boring ones, too. All those sidetracks and dead-ends, the things I leave out of my personal story because they aren’t interesting and didn’t ‘go anywhere,’ they are raised up, too. Because they are me, too. They are my life, and my whole life is what God will raise up after I die.

I don’t really know what this means. But thinking about autobiography helps me understand a little. In A Broad Place, Moltmann includes so many different things, but because he is only human and a book can only be so long, he also leaves out most things. He reflects back on his life, but his vantage point is limited, and he does not draw any grand conclusions about what it all ‘meant.’

But perhaps in the resurrection, God will do what even the best memoirist can’t. Nothing will get forgotten and left out. Nothing will be struck through as irrelevant. There is all the time in eternity to give my life a full hearing, including all the things I have forgotten. And everything will get tied together, so that each moment of my life “coincides in eternity, and becomes one.” What I can’t do- make sense of the whole of my life- God will do, not by trimming down what doesn’t fit but by making it fit into something bigger, into His own life story that He shares with me, and with everyone else. Like six squares folded up into a cube, all the moments of my life will be reconciled, and that will be me. The boring and the shameful moments as well as the momentous and joyful ones, they are all “fully known” to God (1 Cor 13:12), and they will all live again in the power of His resurrection.

There will be no dusty attics in the world to come, where things that don’t matter much get stuck and forgotten because there’s no other place for them. He will make all things new. So there is hope for all of us, and hope for all of each of us. Amen.

Jürgen Moltmann, A Broad Place (Minneapolis: Fortress, 2009), 178.

Jürgen Moltmann, The Way of Jesus Christ: Christology in Messianic Dimensions (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1993), 267-8.

Indeed, indeed! Moltmann really does slap!